Spinal Immobilisation

Pre-hospital spinal immobilisation aims to stabilise the spine by restricting movement, to prevent further injury.

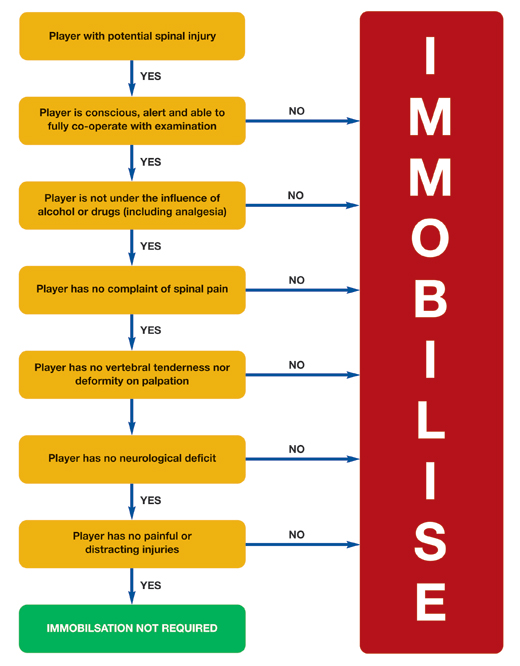

Criteria for Spinal Immobilisation

Spinal immobilisation should be considered in any player with a mechanism for and presenting with signs and symptoms of a spinal cord injury. A flowchart showing the JRCALC guidance on spinal immobilisation (Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee 2006) decision making process is shown below.

Clearing the Spine

If having followed the decision pathway for immobilisation, it is decided that immobilisation is not required then the practitioner may proceed to “clear the spine” on the pitch or the medical room. The procedure recommended by the Faculty follows the Canadian C-Spine Rules (Stiell IG 2001) (C. C. Stiell IG 2003) and those of the NEXUS and NICE recommendations.

Steps to clearing the C-spine:

- No suspicious mechanism of injury

- No reduction in conscious level (GCS 15)

- No neurological signs or symptoms

- No distracting injury

- No midline cervical spine tenderness

- No intoxication with alcohol or drugs

- Able to voluntary rotate neck > 45° R & L

- Able to flex and extend neck

Recommended procedure for clearance of the c-spine:

- While maintaining manual in-line stabilisation (MILS), palpate the cervical and upper thoracic spine for midline tenderness. If there is suspicion of a thoracic or lumbar spine injury then the patient should be log-rolled and the whole spine palpated for midline tenderness.

- If there is no midline tenderness, ask the player to actively slowly rotate their head left and right, then flex and extend their neck but to stop if they experience any of the following:

- Midline pain

- Block to movement

- Any neurological symptoms

- If any of the above occur, the player should move their head back to a neutral position, manual in-line stabilisation should be re-applied and the player will need full spinal immobilisation and transferred to hospital.

- If the player can complete the above, they should be assisted into an upright sitting position and the above process repeated (palpation and movement).

- If at any stage they experience any of the symptoms listed in 2, above, they will need to have full spinal immobilisation applied.

- If they can complete the above, they should be asked to actively, slowly, move their neck through a full range of movements. A full examination of the neck should then be completed including passive range of movements and resisted testing.

Cervical Collars

Evidence suggests that cervical collars reduce motion in all planes but, alone, they do not provide adequate immobilisation they must always be used in conjunction with manual in-line stabilisation (MILS) or head blocks and straps or tape. There is a range of cervical collar sizes available. However, to minimise the number of collars stocked, it seems sensible to use an adjustable collar. This can be adjusted to fit most adult patients. Application of an adjustable cervical collar is detailed in Appendix 1.

The cervical collar needs be in contact with the skin of the chest, posterior thorax, clavicles, and trapezius muscles, to be effective.

Log Roll

The objective of the logroll is to maintain normal anatomical alignment of the spine, and reduce the risk of further damage to the spinal column or cord, while moving the patient.

A logroll may be required in the following circumstances:

- To move the patient from a face down or side lying position to lying on their back

- To position the patient on a split long board or long rescue board

- To roll a patient onto their side, if they start to vomit

The logroll procedure is detailed in Appendix 2.

Immobilisation Devices and Techniques

The traditional method for extrication of a player is using a long (spinal) board. This requires the player to be rolled 90°, the board inserted and patient rolled onto the board. The position of the player on the board can then be adjusted in a co-ordinated way to ensure they are in the centre of the board. This is achieved by either sliding the player down the board and back up at a slight angle or better done by placing the long board higher and only one movement up the board. Once centralised on the board the body straps are applied first, before the head blocks and tapes.

More recent focus has been on split long boards made of thermoplastics such as polypropylene. The rationale for using these devices is to reduce unnecessary movement. When using a traditional long (spinal) board this involves at least 180° rotation to place the injured player on the board and similar movement for removal in the emergency department. The introduction of the split long board only requires two 15° tilts at scene. Patients do still though need to be log rolled in the emergency departments to examine the spine but at least this is in a more controlled environment. In addition the Scoop stretchers take longer to cause the same undesirable pressure ischemia caused by long boards to the soft tissues. The new thermoplastic polypropylene split long boards replace the traditional aluminium scoop stretcher and offer a number of advantages:

- Suitability for heavy players up to 159kg

- Radiolucent

- Reduced patient movement compared to long (spinal) boards

- Ischaemia time of an hour

There are some negatives to consider when using a split long board. The width and height of some players challenge these devices. These devices tend to be narrow ~47cm wide compared to front row forwards who can be up to 70 cm wide. A further issue is the recessed handles which can make gripping for the carry difficult with wider players. The use of a set of strap handles can ease this problem. A further issue is when attempting to carry tall players e.g. second row forwards, can result in their weight being centred on the aluminium extensions. This can be overcome by using a supportive sleeve or a vacuum mattress. See appendix 3.

When a long transport time (>45 minutes) is being undertaken with a patient with a suspected spinal injury, consideration should be given on transport in a vacuum mattress. See appendix 4.

Removal from the field of play should be undertaken by an experienced and well-trained team. Pre-event rehearsal should have taken place before each event/match. The team should carry the injured player feet first in the direction of travel, so the attendant at the head end of the player can see where they are going.

An aid to prevent slipping by the team or dropping the injured player is the use of a bespoke motorised buggy. The use of a buggy removes the risk of carrying often heavy players on slippery surfaces. It is essential for pre-event training to include the appropriate route to the medical room or to an ambulance.