Velocity-based monitoring/training

While GPS data may be useful for assessing workload in conditioning sessions, team-based training and matches, its applications to monitoring workload in the gym are extremely limited. As technology advances, the measurement and monitoring tools that a coach has access to is continually evolving.

Figure 8. Linear position transducer being used to determine velocity, power and force outputs during a quarter squat.

One area of training that has enjoyed a surge in popularity is velocity-based training which involves measuring the velocity of a resistance training exercise. The tools to measure the velocity of resistance exercises have recently become more affordable and easily obtained. Linear position transducers are a common technology used to measure velocity in the gym. According to Jovanovic and Flanagan in 2014, linear position transducers consist of a central processing unit that attaches to the barbell with a retractable measuring cable. This measuring cable measures the displacement of the bar and from this the velocity and acceleration can be calculated. More recently camera-based systems and inertial measurement units which contain accelerometers and gyroscopes have been developed for the tracking of barbell velocity. Velocity measurement devices usually attach to the bar in some way or can be worn by the player.

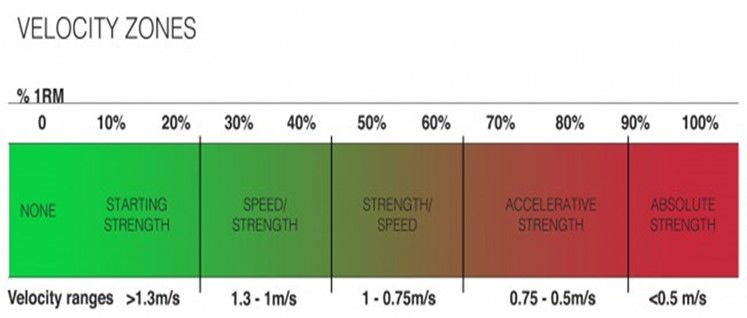

Velocity-based training could be classed as both a training and importantly, a monitoring tool. The percentage-based method for load lifted in resistance training exercises is the most common method used for programming. A percentage of a player’s maximum load that they could possibly lift in the chosen exercise is prescribed in training to target specific adaptations for example 5 sets of 5 repetitions at 85% of 1 repetition maximum in the squat exercise. With the velocity-based approach, certain velocity ranges correspond with certain percentages of 1 repetition maximum load as shown in Figure 7. below. They also correspond with specific types of strength. For example, if a player bench pressed at a velocity of 0.75 m/s, the coach can use this table and identify that they are working at 60% of their 1 repetition maximum load and are targeting strength speed. One real positive of velocity-based monitoring is that this relationship between percentage of 1 repetition maximum or load and the velocity is very stable in simple strength exercises such as the squat and bench press. The relationship holds true regardless of strength level and even after increases or decreases in strength. For example, if 0.8m/s corresponded to 60% of a player’s 1 repetition maximum load, then around 0.8 m/s should always be 60 percent of the athletes 1 repetition maximum, even as they get stronger and can lift more total weight. This stable relationship between load and velocity allows for velocity measures to be used for monitoring the training and as a viable alternative to the traditional percentage-based approach in programming resistance exercise.

Figure 9. Velocity Zones